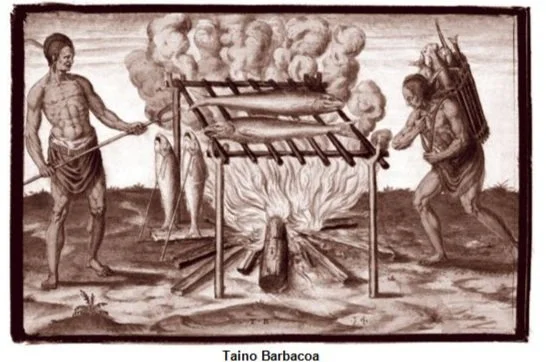

Indigenous Practices

Indigenous peoples in the Americas utilized various slow-cooking techniques for meat, including smoking and slow-roasting, often over open flames or pits. The term “barbecue”, derived from “barbacoa,” is attributed to the Taíno sub-tribe of the Arawak people, an Indigenous group from various Caribbean islands like Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic.

One of the earliest written records of pork barbecue dates back to December 1540 when Hernando de Soto attended a feast with the Chickasaw tribe in Mississippi. Although the account lacks specific cooking method details, it illustrates the cultural blending of Spanish pork and Indigenous practices. While barbacoa involved raised racks, modern pitmasters often utilize earth-dug pits, likely reflecting a practical evolution for cooking larger animals. Food play a central role in Taíno social life and rituals, fostering community bonds. Their culinary practices laid the groundwork for contemporary Caribbean barbecue, preserving a link to Taíno heritage celebrated in festivals and gatherings today.

The African Influence

Early 1600s

Enslaved Africans played a crucial role in shaping barbecue in the Americas, merging their cooking techniques with those of Indigenous peoples. African cooks introduced methods like pit cooking and unique spices, laying the foundation for modern barbecue practices. The intertwined histories of Indigenous peoples and enslaved Africans are pivotal in discussing barbecue heritage.

Mid-1700s

Southern barbecue had developed into a distinctly Black tradition on Virginia plantations, associated with holidays and political gatherings.

1830s

African American cooks were considered essential to authentic barbecue experiences. Despite the celebratory nature of barbecues, they were steeped in the harsh realities of slavery, as plantation owners used these events to portray racial harmony.

The term “pitmaster,” originally referred to an older enslaved cook who oversaw younger slaves in preparing the barbecue, with the first printed reference appearing in 1939. It has since evolved into a title associated with white individuals, but African Americans continued to be the primary laborers in barbecue preparation. Earth-dug pits, a traditional cooking method, remained prevalent in Black communities until the late 20th century, a legacy that underscores the responsibility of current pitmasters to honor their ancestors.

Historical accounts, such as those documented in the 1930s Slave Narratives, reveal the significance of barbecue in the lives of formerly enslaved individuals.

1862

After the Civil War, formerly enslaved individuals like Abby Fisher leveraged their cooking

skills for economic independence. Fisher moved to San Francisco and opened a successful business selling preserves earning a bronze medal for her pickles in 1880. She published What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking in 1881, dictating recipes to others since she was unable to read or write. Though her book doesn’t include barbecue recipes, it features a notable “Game Sauce” that consists of plums, onions, vinegar, sugar, and spices. While many who preserved barbecue traditions post-emancipation faced new challenges such as sharecropping, barbecue practices remained integral to African American culture.

Mrs. M.E. Abrams recounts how she and her enslaved relatives would steal hogs for weekend barbecues, and dress and cook the hogs in a gully, reflecting their culinary ingenuity despite the severe consequences they faced for stealing.

Charles Ball recounted how an overseer punished enslaved people for a stolen hog. When they didn’t confess, about 20 were whipped until one man admitted to it and was subjected to a torturous punishment called “cat-hauling,” where a cat was dragged across his back.

Despite such brutality, barbecues provided moments of celebration; Gus Feaster noted the joy of 4th of July gatherings on plantations, where enslaved people enjoyed barbecued meats and festive activities.

Modern

Generations of Black pitmasters, including Dr. Howard Conyers, have continued to refine their skills, continuing to draw on their ancestors techniques. Unfortunately, the contributions of Black communities to barbecue are still largely overlooked.

Culinary historian Michael Twitty (pictured) notes the disparity in recognition of how his education framed his ancestors as unskilled laborers, despite the profound impact they had on American culinary traditions.

Check out Dr. Howard Conyers’ blog here!

Read more from Michael Twitty on his website Afroculinaria!

Regional Development in the American South

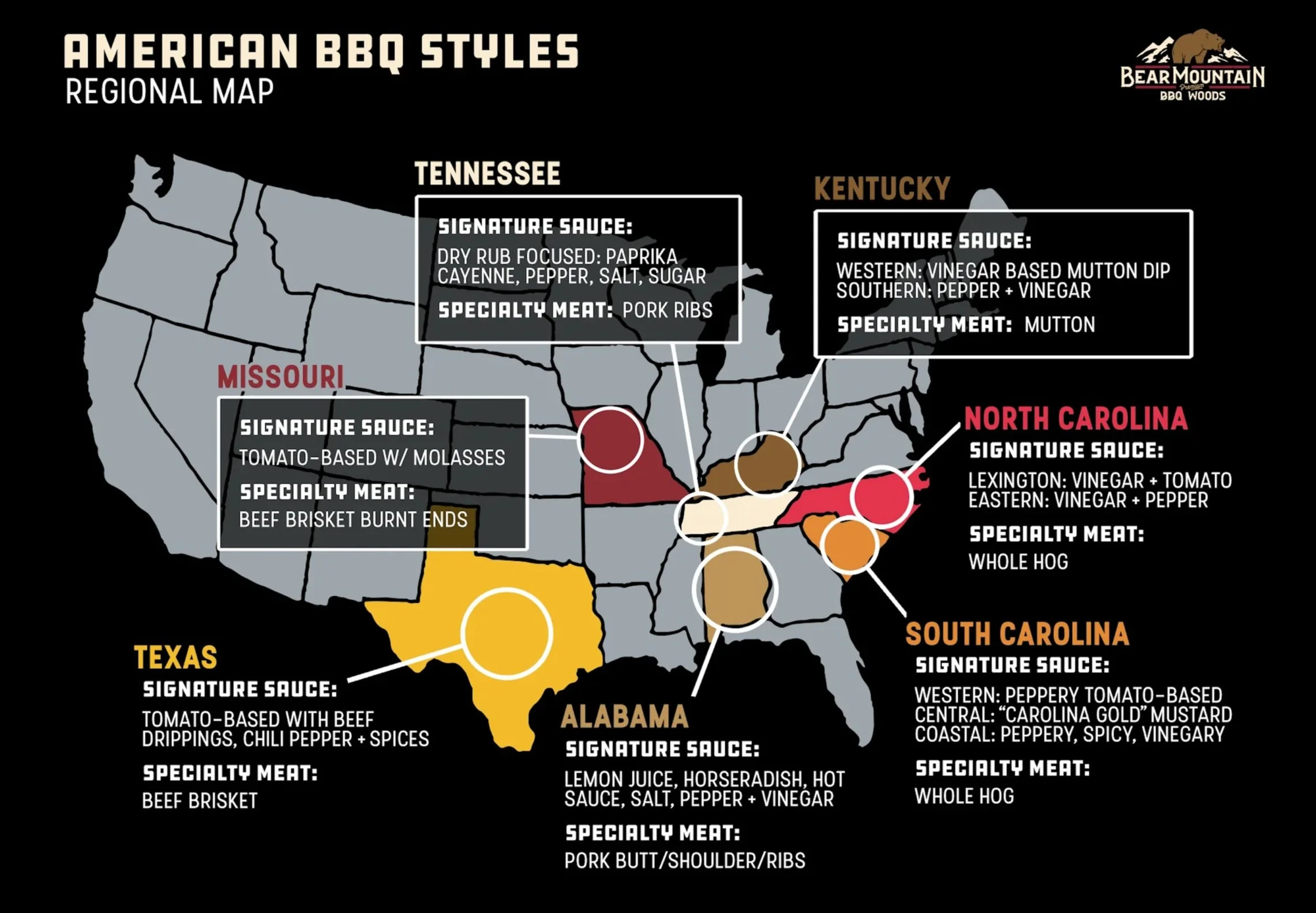

Over time African and Native American influences blended with European flavors, leading to various regional barbecue styles that reflect the country’s complex history of colonization a immigration. Some of the most renowned BBQ regions in the U.S. are Memphis, Kansas City, the Carolinas, and Texas, each with distinct flavors and cooking methods.

Memphis, famous for its pork dishes, like pulled pork sandwiches and ribs, often serve the dishes with secretive sauces and rubs.

West Tennessee is known for whole-hog BBQ, a traditional method that’s at risk of disappearing, but pitmasters like Pat Martin aim to preserve it.

Kansas City uses a variety of meats served in a thick, sweet sauce, a style influenced by Black American chefs.

North Carolina’s BBQ split between Eastern and Western styles, with the Eastern method emphasizing whole-hog cooking and vinegar-based sauce while Western BBQ features a ketchup-based sauce.

In Texas, there are multiple BBQ styles that coexist. Central Texas focuses on beef smoked simply with salt and pepper, while East Texas includes a wider variety of meats served with thick, sweet sauces.

Georgia is where pork reigns supreme, and South Carolina is famous for whole-hog smoking and its mustard-based sauces.

Alabama’s BBQ is distinguished by white sauce made from mayonnaise, while Kentucky offers a mix of meats like mutton, smoked with various sauce Chicago’s BBQ scene features a unique smoking method suited to the city’s climate, using indoor propane tank smokers or wood-burning ovens.

Virginia claims a historical legacy in BBQ, with Northern Virginia known for its sweet tomato-based sauce, Central Virginia offers sweet and so sauces, sometimes with peanut butter or root beer, the Southside/Tidewater region features a vinegary tomato sauce with mustard, and the Shenandoah Valley has herbaceous vinegar sauces. Virginians say they don’t “smoke” meat, they “barbecue” it.

This rich tapestry of regional BBQ styles not only highlights the vast diversity across the U.S. but also emphasizes the cultural influences that have shaped this culinary tradition.

Read more about Regional Barbecue here.