In Little Shop of Horrors, the musical stylings reflect the era and themes of the story, blending various genres. Set in a nostalgic 1960s atmosphere, the musical incorporates elements of doo-wop, rhythm and blues, and Broadway show tunes.

Diving Deeper | LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS: Science Fiction, Satire, and the Cult of the Killer Plant

Diving Deeper | Broadway Musicals: A Jewish Legacy

Diving Deeper | How LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS Shaped Disney’s Renaissance

Little Shop of Horrors remains a global phenomenon, largely propelled by the success of the 1986 film directed by Frank Oz. The musical continues to thrive in its current Off-Broadway revival. Its triumph led producer David Geffen to introduce songwriting duo Howard Ashman and Alan Menken to Disney executives, paving the way for their pivotal role in the Disney Renaissance.

FAT HAM Diving Deeper: HAMLET Walkthrough

Hamlet deals with questions about life and existence, sanity, love, death, and betrayal. It is one of the most quoted works of literature in the world, and since 1960 it has been translated into 75 languages (including Klingon).

Summary:

In Hamlet, the ghost of King Hamlet urges his son to avenge his murder by killing Claudius, the uncle who usurped the throne. Prince Hamlet feigns madness, grapples with existential questions, and plots revenge, while Claudius schemes against him. The play culminates in a tragic duel where the King, Queen Gertrude, Laertes, and Hamlet all perish.

The story begins at Elsinore Castle, where guards spot King Hamlet’s ghost. The ghost reveals to Hamlet that Claudius murdered him, spurring Hamlet to seek vengeance while pretending insanity. Hamlet stages a play to confirm Claudius's guilt, causing Claudius to flee in guilt. Sent to England under a secret death warrant, Hamlet outmaneuvers the plot and returns to Denmark.

Meanwhile, Ophelia, devastated by her father’s death and Hamlet’s rejection, drowns in madness. At Ophelia’s funeral, Hamlet confronts her brother Laertes, leading to a duel orchestrated by Claudius. The plan backfires: Gertrude drinks poison meant for Hamlet, Laertes and Hamlet wound each other fatally, and Hamlet kills Claudius before dying. Horatio survives to recount the tale as Fortinbras arrives to take the throne.

The Action Begins Otherworldly

At the start of the play, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, encounters a ghost resembling his recently deceased father. The ghost reveals that King Hamlet was murdered by Claudius, the king’s brother, who seized the throne and married Queen Gertrude. The ghost urges Hamlet to avenge his death by killing Claudius.

Royal Shakespeare Company, photo by Manuel Harlan

This burden deeply troubles Hamlet. He wrestles with the ghost’s intentions, questioning whether it might be an evil spirit luring him into eternal damnation. Hamlet’s doubt, grief, and inner turmoil make him one of literature’s most psychologically complex characters. Though slow to act, his decisions are often impulsive and violent, as seen in the famous "curtain scene," where he mistakenly kills Polonius.

Hamlet’s Love

Polonius’ daughter Ophelia is in love with Hamlet, but their relationship has broken down since Hamlet learned of his father’s death. Ophelia is instructed by Polonius and Laertes to spurn Hamlet’s advances. Ultimately, Ophelia dies by suicide as a result of Hamlet’s confusing behavior toward her and the death of her father.

Royal Exchange Theatre, Jonathan Keenan Photography

A Play Within a Play

In Act 3, Scene 2, Hamlet organizes actors to re-enact his father’s murder at the hands of Claudius to gauge Claudius’ reaction. He confronts his mother about his father’s murder and hears someone behind the arras. Believing it to be Claudius, Hamlet stabs the man with his sword. It transpires that he has actually killed Polonius.

American Conservatory Theater

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern

Claudius, sensing Hamlet's threat, declares him mad and sends him to England with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who report on Hamlet’s behavior. Secretly, Claudius orders Hamlet’s execution upon arrival, but Hamlet escapes, altering the orders to condemn Rosencrantz and Guildenstern instead.

Royal Shakespeare Company, 1965

To Be or Not to Be …

Hamlet arrives back in Denmark just as Ophelia is being buried, which prompts him to contemplate life, death, and the frailty of the human condition. The performance of this soliloquy is a big part of how any actor portraying Hamlet is judged by critics.

Young Vic, photo by Helen Murray

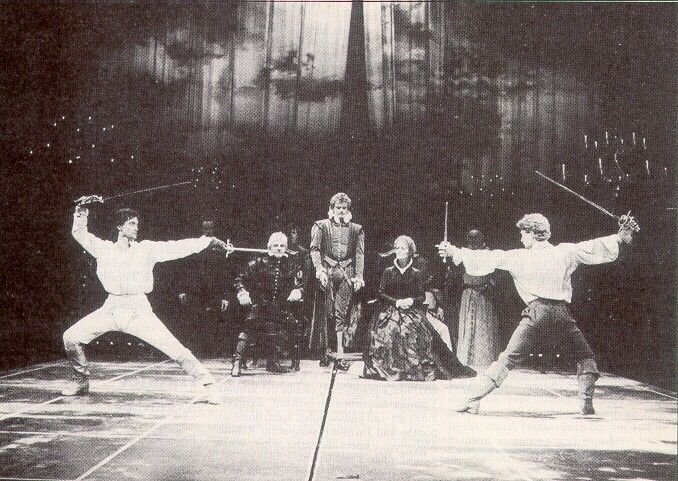

Tragic Ending

Laertes returns from France to avenge the death of Polonius, his father. Claudius plots with him to make Hamlet’s death appear accidental and encourages him to anoint his sword with poison. He also puts a cup of poison aside, in case the sword is unsuccessful.

In the action, the swords are swapped and Laertes is mortally wounded with the poisoned sword after striking Hamlet with it. He forgives Hamlet before he dies.

Gertrude dies by accidentally drinking the cup of poison. Hamlet stabs Claudius and forces him to drink the rest of the poisoned drink. Hamlet's revenge is finally complete. In his dying moments, he bequeaths the throne to Fortinbras and prevents Horatio's suicide by imploring him to stay alive to tell the tale.

Michael Twitty's Apple Barbecue Sauce

Michael W. Twitty is a food writer, independent scholar, culinary historian , and historical interpreter personally charged with preparing, preserving and promoting African American foodways and its parent traditions in Africa and her Diaspora and its legacy in the food culture of the American South. Michael is a Judaic studies teacher from the Washington D.C. Metropolitan area and his interests include food culture, food history, Jewish cultural issues, African American history and cultu ral politics. Afroculinaria will highlight and address food’s critical role in the development and definition of African American civilization and the politics of consumption and cultural ownership that surround it.

Blog: Afroculinaria - afroculinaria.com

Twitter: @Koshersoul

Instagram:@thecookinggene

Michael W. Twitty on Facebook

APPLE BARBECUE SAUCE

For chicken or salmon or sliced pot roast or lamb, brisket or spicy roasted vegetables…

Ingredients:

1/2 cup of chopped Vidalia onion or any sweet onion

1/4 cup of minced celery

1/4 cup of minced carrot

1 tablespoon of minced garlic

1 teaspoon of crushed minced ginger.

1 teaspoon of kosher or sea salt

2 tablespoons of the pareve oil

3/4 cup of tomato paste

1/2 cup of apple juice or apple cider

1/2 cup of grated Granny Smith or Honeycrisp apple or 1/2 cup of applesauce (unpretty apples are great for this!)

1/2 cup of apple butter

1/2 cup of apple cider vinegar

1/4 cup of low sodium soy sauce

1/4 cup of brown mustard

1/2 cup of light brown sugar

1 teaspoon of kitchen pepper (see my book)

1 teaspoon of sweet paprika

1 teaspoon of small coarse Black pepper

1 teaspoon of seasoned salt of your choice

Sauté onion, minced celery, minced carrot, minced garlic, crushed minced ginger, kosher or sea salt, pareve oil together in a large saucepan over medium-low heat until onion and celery are translucent. Be attentive! Don’t let it burn.

Mix together cup of tomato paste and apple juice or cider then add to saucepan

Add grated apple or applesauce, apple butter, apple cider vinegar, low sodium soy sauce, brwn mustard, light brown sugar, pepper, sweet paprika, black pepper, seasoned salt to saucepan.

Stir and stir and bring to a quick boil. Please lower heat and cover. Stir every 5 minutes for 45 minutes.

Adjust to taste.

You can find this recipe on Michael’s blog here.

The History of American Barbecues

Sizzling Shakespeare: A Deep Dive into the Southern Charm and Queer Spirit of Fat Ham

Virginia Stage Company was honored to correspond with playwright James Ijames just before the rehearsal began for his masterful and transformative play FAT HAM on The Wells Theatre stage. Come learn more about the show, it’s reach history and humor, and what audiences of Hampton Roads can uniquely benefit from with this show!